Following the scent of roses blooming

on a residential street, I explore the town area of Haramachi, stopping at an

ochre-colored wall. Inside, I find Hosshinji, a 1631 Zen temple affiliated with

Engakuji in Kamakura.

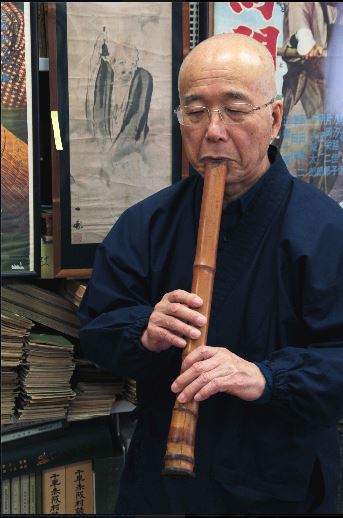

Priest Daitetsu Kosuge, 73, waves me

inside, where he promptly prepares me some thick green tea. The wind outside

and the swish of the bamboo chasen (whisk) frothing the tea mingle

nicely.

In conversation, I gradually learn

that Kosuge harbors a special passion for the bamboo shakuhachi flute,

an integral part of the Fuke-shu sect of Zen Buddhism. “Monks once practiced suizen,

a form of prayer through playing basic meditative pieces, which were known as

the honkyoku,” he explains. “These monks — many of whom were samurai

that had lost their commissions once Japan was unified under the Tokugawa

shogunate — were known as komuso.”

Throughout the Edo Period (1603 —

1868), komuso, wearing their distinctive tengai (a woven bamboo or

rattan hood meant to render their own egos void), were offered rare license to

wander across the country’s borders freely, so as to visit other temples and

sustain their mendicant lifestyle. Kosuge suggests it might have been this

freedom of movement, plus their samurai training and secretive hood, which led

many to suspect the Komuso of moonlighting as spies for the shogunate.

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 greatly

curtailed the practice of Buddhism in favor of the Imperially-preferred Shinto

religion, and the practices of Komuso monks were banned. “The main Komuso

temple was only about 2 km from here,” Kosuge says, “So many of the monks took

refuge in this temple.” I contemplate the horror of being an egoless priest,

only to have even that practice voided.

Seeing that I’m keen on the subject,

Kosuge guides me to a temple room where he has stored more than twenty

shakuhachi. He plucks one off the rack, and as his breath enters the bamboo,

the sound blows away the afternoon. For all its overuse in documentaries and by

restaurants hoping to evoke a taste of Japan, to hear a well-played shakuhachi

in person is stirring.

Kosuge next shows me upstairs to his

museum of shakuhachi, Komuso songbooks, rare ephemera, woodblock prints and

unusual flutes. After the Meiji Era, the shakuhachi was taken up as a purely

musical instrument, but Kosuge sees a revival of interest in the classical

pieces these days, too.

At last, I (journalist Kit Nagamura) request a try at the

flute, ignoring the sexual innuendo often associated with women and shakuhachi.

Kosuge laughs as I struggle to establish an effective embouchure. When a note

purls out, it feels, frankly, as though my whole soul follows it as it floats

off. Kosuge nods. This makes sense to him.

I could blow off the rest of the day

with Kosuge, but knowing he must be busy, I excuse myself. Heading back toward

Okubo Avenue, the priest’s gentle humor and hospitality lingers like notes

well-played.