Maintain a loose flexibility in these three movements demonstrated, work each hand at the same time. Eases the tension and pain of repetitive motion, as occurs, for example, in playing a musical instrument. Also, play with a light grip; think of the fingers as feathers, using an effortless fluid expansion.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Sunday, January 24, 2010

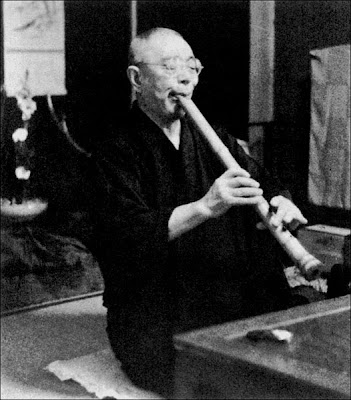

Koizumi Shizan Calligraphy

Koizumi "Ryoan" Shizan, 38th Abbot of Meian-ji from 1953, was said to have "enhanced" the honkyoku that Higuchi Taizan had collected possibly by organizing them into the teaching regimen of 32 honkyoku,with it's levels of achievements and ability, similar to the same system found in the Kinko-ryu. He also notated and published them in the form that exists today.

Morimasa "Seisui" Horiuchi; Quiet Water

The monument marker erected in the 1960's at the Asahi Waterfall; the inspiration for Taki Ochi. Sensei Morimasa Horiuchi's name is engraved on the back of the monument as Seisui Horiuchi, along with his good friend Yushin Kuniyoshi and other Taizan-ha notable players. Seisui translates as "Quiet Water" and Yushin as "Spirit Heart". Tomimori Kyozan gave Mori-san his Taizan-ha name. Kyozan Sensei's student is a calm, gentle, humorous person with all the power and flexibility of water's nature. He doesn't use the name but there it is...

The monument marker erected in the 1960's at the Asahi Waterfall; the inspiration for Taki Ochi. Sensei Morimasa Horiuchi's name is engraved on the back of the monument as Seisui Horiuchi, along with his good friend Yushin Kuniyoshi and other Taizan-ha notable players. Seisui translates as "Quiet Water" and Yushin as "Spirit Heart". Tomimori Kyozan gave Mori-san his Taizan-ha name. Kyozan Sensei's student is a calm, gentle, humorous person with all the power and flexibility of water's nature. He doesn't use the name but there it is...Sensei Seisui has a nice ring like a clear bell.

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Kumamoto Shakuhachi Festival

Kumamoto, Japan; February 14th at Sojo Daigaku Hall, Kumamoto Shimin Kaikan from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm. Workshops in Myoan koten honkyoku, Kinko honkyoku, Tozan honkyoku and Gendai. Shakuhachi performances in the evening.

Thanks to the efforts of Jeff Cairns, pictured at right in group poster.

Further the resurgence of shakuhachi kinship.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

Dòngxiāo Proficiency Before Shakuhachi

Old Taizan-ha instruction 簫 then 尺八

Higuchi Taizan recognizes Juzan Ikeda for excellence in playing the dòngxiāo.

Higuchi Taizan recognizes Tanikita Muchiku for excellence in playing the dòngxiāo.

Also, next generation Tomimori Kyozan was taught by Shizan Kobayashi initially on the dòngxiāo instead of the shakuhachi. Perhaps this Myoan tradition honored an even older Chinese influence; hearing in practice the tone progression of instrumental history.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

American Shakuhachi Composition from 1946

Composer Henry Cowell plays some shak for Frank Zappa's favorite composer Edgar Varese.

Composer Henry Cowell plays some shak for Frank Zappa's favorite composer Edgar Varese.The idea of a western composer writing for shakuhachi was not an entirely new idea in the 1970s, but precedents were few and far between. Henry Cowell was probably the first, with a piece called The Universal Flute written in 1946. After World War II a few Japanese composers wrote music for shakuhachi, most notably Makato Moroi and later Toru Takemitsu, and the idea of the integration of the shakuhachi into the western instrumentarium began to take hold (with even an occasional rock band using the instrument). Frank Denyer's first works he produced for the instrument (On, on – it must be so and Wheat) were essentially solo works with accompanying parts for percussion. They are very different from the traditional Japanese repertoire and manner of playing, and yet far also from the concerns of most contemporary composers of the time. Rather than being exercises in cultural fusion they are musical spaces not yet identified on any map. (Bob Gilmore/Frank Denyer)

AIR: Music for Multiple Shakuhachi January 20, 2006

Ralph Samuelson

Elizabeth Brown

Ned Rothenberg

Shoji Mizumoto

Music by Henry Cowell, Ned Rothenberg (premiere), Frances White, and Elizabeth Brown (premiere), plus traditional shakuhachi music, including Shika no Tone and Chidori .

Believing you could find the world in a single tone, the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism chose the blowing of the shakuhachi as their chief spiritual practice. In their Honkyoku, or original music, phrases are the length and shape of a breath, and the sound of the breath is a central, defining element.

The shakuhachi is a traditional Japanese bamboo flute whose haunting, vocal sound is capable of infinite nuance. In this program, both traditional Honkyoku and newer pieces will be performed by one, two, three or four players, positioned around the room. Sound will travel over and through the audience from different directions, meeting and mixing in the air over their heads.

Also, another perspective of reference, Peter Garland mentions that "frequently the “self-taught” composer has as many — or more — teachers than the more normal conservatory-manufactured ones. And that this teaching and learning do not end with the bestowing of a musical diploma, but rather can continue over an entire lifetime, and in some unusual ways and contexts. John Cage attending D.T. Suzuki’s classes on Buddhism at Columbia in the early 1950’s is a classic example. Or Lou Harrison studying Javanese gamelan with Jody Diamond when he was already in his sixties and had built and written wonderful music for his own and Bill Colvig’s American Gamelan. Cowell had numerous teachers throughout his life, especially connected with his studies of non-European musics. I love the photos of Cowell playing shakuhachi for an attentive Edgard Varèse, and of Henry trying out a Sri Lankan drum with a native musician in Colombo in 1957 — for Cowell learning was a lifelong process. In my own case, my teachers, along with Budd and Tenney, have included Dane Rudhyar, Philip Corner, Harrison and Nancarrow; also (at Cal Arts) teachers of American poetics, anthropology, performance art and video, and Asian music. Other teachers have included a Javanese shadow puppet master, a Pure pecha Indian maskmaker in Michoacan, a Pitjantjajara elder and singer in Australia, and a legendary jarocho singer and tambourine virtuoso in Veracruz. That’s a lot of teachers for a “self-taught” composer! In each case, it’s a matter of us searching out the knowledge that was needed at the time (and place). There’s a Zen saying that when there is a need and one is ready, a teacher will appear. I would suggest that this is a more courageous path to follow than simply entering the “degree factory.” Though of course those diplomas are redeemable at any number of grant institutions and prize committees — places where free-thinking (i.e. “selftaught”) individuals are not so welcome."

ID *LT-10 7182 Japan. Shakuhachi performances.

1 sound disc, 78 rpm, aluminum-based, mono. ; 10 in.

On label: J 2-1, J 2-2.

Total duration: 4:24.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 308.

ID *LT-10 7183 Japan. Shakuhachi performances.

5 sound discs, 78 rpm, aluminum-based acetate, mono. ; 10 in.

Duration: 28:50.

Performer: G.K. Tamada.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 330, *LJ-10 331, *LJ-10 332, *LJ-10 333, *LJ-10 334.

ID *LT-10 7184 Japan. Shakuhachi performances, November 30, 1941.

1 sound disc, 78 rpm, paper-based acetate, mono. ; 10 in.

Performer: G.K. Tamada.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 325.

Contents: Nezasa School. Shirabe : Introduction to prayer (2:29) -- Fuke School. Chosi (3:44).

Henry Cowell's shakuhachi records now available at the New York Public Library.

AIR: Music for Multiple Shakuhachi January 20, 2006

Ralph Samuelson

Elizabeth Brown

Ned Rothenberg

Shoji Mizumoto

Music by Henry Cowell, Ned Rothenberg (premiere), Frances White, and Elizabeth Brown (premiere), plus traditional shakuhachi music, including Shika no Tone and Chidori .

Believing you could find the world in a single tone, the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism chose the blowing of the shakuhachi as their chief spiritual practice. In their Honkyoku, or original music, phrases are the length and shape of a breath, and the sound of the breath is a central, defining element.

The shakuhachi is a traditional Japanese bamboo flute whose haunting, vocal sound is capable of infinite nuance. In this program, both traditional Honkyoku and newer pieces will be performed by one, two, three or four players, positioned around the room. Sound will travel over and through the audience from different directions, meeting and mixing in the air over their heads.

Also, another perspective of reference, Peter Garland mentions that "frequently the “self-taught” composer has as many — or more — teachers than the more normal conservatory-manufactured ones. And that this teaching and learning do not end with the bestowing of a musical diploma, but rather can continue over an entire lifetime, and in some unusual ways and contexts. John Cage attending D.T. Suzuki’s classes on Buddhism at Columbia in the early 1950’s is a classic example. Or Lou Harrison studying Javanese gamelan with Jody Diamond when he was already in his sixties and had built and written wonderful music for his own and Bill Colvig’s American Gamelan. Cowell had numerous teachers throughout his life, especially connected with his studies of non-European musics. I love the photos of Cowell playing shakuhachi for an attentive Edgard Varèse, and of Henry trying out a Sri Lankan drum with a native musician in Colombo in 1957 — for Cowell learning was a lifelong process. In my own case, my teachers, along with Budd and Tenney, have included Dane Rudhyar, Philip Corner, Harrison and Nancarrow; also (at Cal Arts) teachers of American poetics, anthropology, performance art and video, and Asian music. Other teachers have included a Javanese shadow puppet master, a Pure pecha Indian maskmaker in Michoacan, a Pitjantjajara elder and singer in Australia, and a legendary jarocho singer and tambourine virtuoso in Veracruz. That’s a lot of teachers for a “self-taught” composer! In each case, it’s a matter of us searching out the knowledge that was needed at the time (and place). There’s a Zen saying that when there is a need and one is ready, a teacher will appear. I would suggest that this is a more courageous path to follow than simply entering the “degree factory.” Though of course those diplomas are redeemable at any number of grant institutions and prize committees — places where free-thinking (i.e. “selftaught”) individuals are not so welcome."

ID *LT-10 7182 Japan. Shakuhachi performances.

1 sound disc, 78 rpm, aluminum-based, mono. ; 10 in.

On label: J 2-1, J 2-2.

Total duration: 4:24.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 308.

ID *LT-10 7183 Japan. Shakuhachi performances.

5 sound discs, 78 rpm, aluminum-based acetate, mono. ; 10 in.

Duration: 28:50.

Performer: G.K. Tamada.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 330, *LJ-10 331, *LJ-10 332, *LJ-10 333, *LJ-10 334.

ID *LT-10 7184 Japan. Shakuhachi performances, November 30, 1941.

1 sound disc, 78 rpm, paper-based acetate, mono. ; 10 in.

Performer: G.K. Tamada.

Access to original items restricted.

Original in: *LJ-10 325.

Contents: Nezasa School. Shirabe : Introduction to prayer (2:29) -- Fuke School. Chosi (3:44).

Henry Cowell's shakuhachi records now available at the New York Public Library.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)